She spotted Chang Sacha, the baker, pushing through the crowd in her flour-coated apron. The inconvenience of having to swarm around the writhing bodies stirred grumbles from the shoppers, and Cinder adored the children for it.Ĭinder’s amusement wilted. But she did love the glares from passersby as the giggling children fell over in their paths. Not so much at the nursery rhyme, a phantom song about pestilence and death that had regained popularity in the past decade.

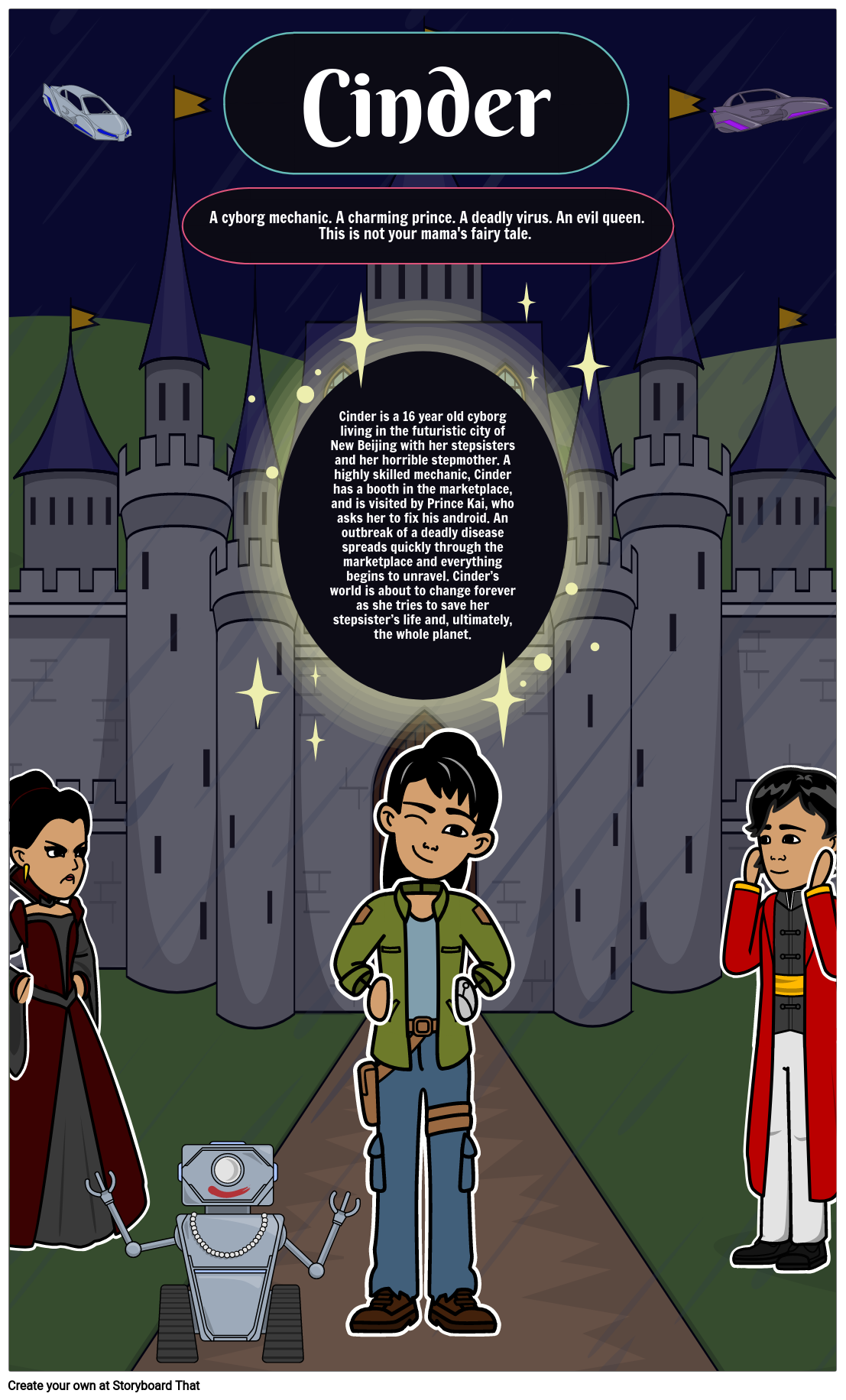

A ring of children were standing just outside her booth, trilling-“Ashes, ashes, we all fall down!”-and then laughing hysterically as they collapsed to the pavement.Ī smile tugged at Cinder’s lips. The netscreens that covered every building and filled the air with the chatter of advertisements, news reports, gossip.Ĭinder’s auditory interface dulled the noise into a static thrumming, but today one melody lingered above the rest that she couldn’t drown out. The hum of ID scanners and monotone voice receipts as money changed accounts. The bellows of men as they bargained with robotic shopkeepers, trying to talk the computers down from their desired profit margins. The square was filled with shoppers and hawkers, children and noise. Cinder knew they really just didn’t like being next to her.Ī stained tablecloth divided Cinder from browsers as they shuffled past. It was squeezed into a shady cove between a used netscreen dealer and a silk merchant, both of whom frequently complained about the tangy smell of metal and grease that came from Cinder’s booth, even though it was usually disguised by the aroma of honey buns from the bakery across the square. Without a sign, her booth hinted at her trade only by the shelves of stock android parts that crowded the walls.

She just hoped Iko would be back soon with its replacement.Ĭinder was the only full-service mechanic at New Beijing’s weekly market. Having loathed the too-small foot for four years, she swore to never put the piece of junk back on again. A sense of release hovered at the end of those wires-freedom. A spark singed her fingertips and she jerked away, leaving the foot to dangle from a tangle of red and yellow wires. Tossing the screwdriver onto the table, Cinder gripped her heel and yanked the foot from its socket.

By the time it was extracted far enough for her to wrench free with her prosthetic steel hand, the hairline threads had been stripped clean. Her knuckles ached from forcing the screwdriver into the joint as she struggled to loosen the screw one gritting twist after another. THE SCREW THROUGH CINDER’S ANKLE HAD RUSTED, THE engraved cross marks worn to a mangled circle.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)